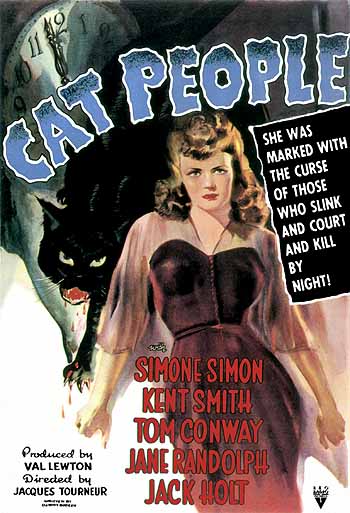

How much ‘noir’ is there in Cat People?

A short paper by Maikel Aarts

0319554

Introduction

There has been a lot of discussion about the actual existence of film noir: some claim it is a genre, others call it a style or a mood and some deny its existence altogether. Among the people who accept there was a certain phenomenon that has been now termed film noir, Jacques Tourneur’s ‘Out of the Past’ (1947) is very often considered a classic film in the film noir style. In this paper I want to see if the various aspects that have often been applied to film noir, can also be seen in an earlier film of Tourneur, 1942’s ‘Cat People’, a film Tourneur directed for producer Val Lewton and in which several of the typical film noir elements can be seen. While it is a horror film and doesn’t have (at least on the surface) standard noir staples like a hard-boiled detective, a femme fatale, organized crime and a complex narrative, it does feature the paranoid social space and the pessimistic worldview so often connected with film noir. Moreover, a lot of the stylistic touches from ‘Out of the Past’, which now are readily associated with film noir, can be traced back to ‘Cat People’. But what exactly makes a film noir a film noir? How many of the features must a film have before it can be termed as film noir? And are some features more determining than others? Building on Marc Vernet’s idea that film noir is ‘a collector’s idea’ (you can always add a film to the list of film noirs or remove one from it), I will try to read ‘Cat People’ as a film noir, in an attempt to see if I’m able to transform a film that’s always been regarded as a horror film into a film noir. I realize that this paper is much too short for an in-depth study or analysis, so I’m sometimes forced to make hasty conclusions and I don’t have time to go into specific aspects at length. As such, this is not an attempt to ultimately transform ‘Cat People’ into a film noir, but more an exercise of my own to see how stable or unstable the term film noir now really is.

The visual style of Cat People

A lot has been said about the visual style of film noir. First, I want to single out a couple of key scenes from ‘Cat People’ that display a distinct film noir sensibility. See the appendix for some screenshots.

As the first example I want to talk about the famous scene in which Irena pursues Alice in the street, which was to be the first of the now famous ‘Val Lewton walks’ (in which one of the protagonists takes a walk through a threatening environment, in which the threats are often both physical as psychological). This scene looks like it could have been lifted straight out a noir. Shadows play a very large role here and director Jacques Tourneur and his cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca (who was also going to be the director of photography on ‘Out of the Past’) give us a showcase of a noir-like play of light and dark. Shadows abound and the lightning is manipulated to such a degree it creates a very foreboding sphere. Sound is particularly important: no music, but only the tapping of the high heels on the pavement, adding a paranoiac feel to the whole. A very nice touch is the filming of the legs of the two women, nicely building up the tension of the scene. The editing also plays a large role here, crosscutting between shots of the hunter and the hunted. There is a beautiful shot where Alice stops at a light post and looks behind her. We see a tunnel behind her that is rendered an eerie passageway (almost like a gate of hell) through the cinematography: a soft filter seemed to be used and there is a slight feeling of rain, which, in combination with the chiaroscuro lighting, gives the shot a very ‘noirish’ feeling (see pictures 1 and 2). The scene climaxes in brilliant fashion with the arrival of a bus, providing one of the greatest scares of the film.

The second scene is perhaps the film’s most famous one: the swimming pool scene. The tension starts when Alice is in the dressing room. She sees a black cat and then hears some noises. Tourneur inserts a very noir-like shot with a shot of the staircase: the banister and balusters of the staircase cast very large shadows on the wall, an image that keeps cropping up in film noirs and keeps in line with what Paul Schrader called ‘the preference for vertical lines of horizontal ones’. Alice turns out the lights and the room is now completely dark, giving a similar shot of the staircase even more emphasis, because now it’s seen from the dark (see picture 3).

A cat-like shadow is seen on the wall, a gesture that will return several more times in this particular scene. The now frightened Alice jumps in the pool and the water makes ghostly reflections on the walls, again a showcase for the innovative cinematography of Musuraca. Just like in the pursue scene, the tension is largely created by the immaculate editing of Mark Robson, alternating between the frightened face of Alice and the water reflections on the wall, complete with eerie shadows.

A cat-like shadow is seen on the wall, a gesture that will return several more times in this particular scene. The now frightened Alice jumps in the pool and the water makes ghostly reflections on the walls, again a showcase for the innovative cinematography of Musuraca. Just like in the pursue scene, the tension is largely created by the immaculate editing of Mark Robson, alternating between the frightened face of Alice and the water reflections on the wall, complete with eerie shadows.

A third example of film noir visuals in ‘Cat People’ that I would like to focus on, is the staircase that leads to Irena’s apartment. This set was actually a left-over set from Orson Welles’s ‘The Magnificent Ambersons’, but it’s filmed in a way that would become commonplace is dozens of later noirs. Shooting from several strange angles and again employing distinctive lightning results in giving this relatively harmless place a strange and threatening edge. A nice contrast appears in two scenes shot at the same staircase: the first appears near the beginning of the film and the second near the end. When we first encounter the staircase, everything looks normal and harmless: there are no shadows and the shot is filmed from a normal angle. When we see the same staircase again later in the film (when it’s clear there’s something wrong with Irena), the exactly same staircase is now transformed into an area of doom and gloom, particularly because of the shadows, that cast an eerie spell over it (see picture 4).

When talking about the use of light and shadow in ‘Cat People’ I would like to concur with Jaime N. Christley, in his discussion of Val Lewton’s films on the mailing list ‘a_film_by’. He wrote: ‘In a Lewton film the sunlit and lamp lit scenes are one with the shadows they create: you can never really go outside in a Lewton film because inside and outside in Lewton mean the same thing. Light and shadow are inextricably linked to one another - when a character walks through a well-lit street in daytime or nighttime, or for that matter in an underground subway, the light might as well be shadow for all the comfort it provides.’ This is of course also true for ‘Cat People’, where light and shadow are totally intertwined, a place for both comfort (Irena) and fear (the rest of the characters). A link between Lewton’s (and Tourneur’s) use of light and shadows and film noir’s can easily be made, because a lot of the aforementioned characteristics are often cited when addressing the visual style of film noir. Actors disappear into shadows or fragmented into shards of lightning, darkness is always around the corner, lightning often comes in form of odd shapes and the action is set in a major city. The compositional tension Schrader talks about is especially visible here, because ‘Cat People’ always prefers a cinematic solution to physical violence or action. So I think I can safely conclude that the visual style of ‘Cat People’ has very much in common with film noir, and can either be seen as an early example of film noir, or as a precursor to it.

Cat People and Paul Schrader

Paul Schrader talks about ‘post-war realism’ in his piece ‘Notes on Film Noir’. While ‘Cat People’ is in many aspects the exact opposite of realism (most clearly in the supernatural elements), it can also be seen as realistic in the way it treats it’s supernatural subject. Where almost every horror film up to this point uses special effects in order to create convincing monsters, ‘Cat People’ famously refrains from this. Yes, the low budget presumably had a lot to do with this decision, but the whole film breathes the same kind of realism that characterize most film noirs (at least according to Schrader). It’s as much a tale of impossible love and the inability to open oneself up to another human being, as it is a tale of giant cats or supernatural involvement.

A lot has been said about the predetermined fate and the all encompassing hopelessness of film noir, something than can be clearly seen in ‘Cat People’: Both Irena and Oliver seem unable to do something about Irena’s condition and they are mere puppets in the whole scheme of things. They undergo, rather than act. To quote Paul Schrader: ‘thus film noir’s technique emphasize loss, nostalgia, lack of clear priorities, insecurity’. This is most certainly true for ‘Cat People’: Irena doesn’t want to look into the future, because she doesn’t know how she can learn to cope with her mental illness. She’s afraid to hurt herself and anyone she loves, she feel completely insecure and doesn’t really know how she can resolve her situation.

Cat People seen in context of Slavoj Žižek’s film noir universe

In his piece ‘Why Are There Always Two Fathers?’, Slavoj Žižek discusses film noir in relation to the theories of Jacques Lacan. I will now try to apply these theories to ‘Cat People’. For Žižek, the defining characteristic of film noir is that the Symbolic Order is thrown out of order. The otherwise neutral and benevolent space has become threatening, corrupt and dangerous. To quote Žižek: ‘What one should bear in mind here is that this neutrality of the symbolic order functions as the ultimate guarantee for the so-called ‘sense of reality’: as soon as this neutrality is smeared, ‘external reality’ itself loses the self-evident character of something present ‘out there’ and begins to vacillate, i.e., is experienced as delimited by an invisible frame: the paranoia of the noir universe is primarily visual, based upon the assumption that our vision of reality is always already distorted by some invisible frame behind our backs’ (Žižek, 152). We can apply this very well to ‘Cat People’, because in this film the Symbolic Order is clearly out of order and the paranoia is clearly established in a visual way. It’s perhaps ironic to say this about a film of which it’s become a cliché to talk about the fact that ‘you don’t actually see anything, it only suggests’, but I think it’s a perfectly valid point to make. After all, Tourneur and Musuraca build up the tension and the sense of paranoia in a purely visual way, externalizing the character’s deepest fears. ‘Cat People’ not only distorts reality, it also frames it’s characters in shadows. The symbolic order in ‘Cat People’ is a strangely distorted world, where everything is deceptively simple: nothing is what it seems.

The story is told from the perspective of it’s three protagonists, Irena, Oliver and Alice and the character of Irena is of particular interest here, because her symbolic order has especially gone haywire. She lives in a world of constant fear, and fears everyone because every touch or sign of affection can lead to her transformation into a cat. Her own inner world is one of constant confusion, because she can’t control her own condition. It’s something that she has to cope with, which she can’t. On the other hand should everyone else be afraid of her, because she is a mortal thread to everyone, but they don’t know it (not until it is too late anyway). So there is no neutral space in ‘Cat People’, neither in Irena’s own inner world, neither in the world around her. Irena’s identity is threatened by the paranoid social space, because her inability to be loved is at the core of all her problems.

The paternal signifier which becomes ‘the obscene father’ in Žižek’s theory poses a problem in relation to ‘Cat People’. There is no real ‘obscene father’ in this film, but I think you can say that Irena’s father (or at least his early death, which is mentioned in the film) functions in part as the ‘obscene father’. His early death is, in part, responsible for Irena’s demons, so you can say that the absence of a true paternal signifier in a way becomes the ‘obscene father’; the symbolic order is thrown out of order, exactly because the lack of the paternal signifier. His absence lies at the basis (this is at least suggested) of all Irena’s mental problems.

When we consider Žižek’s conception of the femme fatale, some difficulties arise. We have two obvious candidates for the femme fatale, Irena and Alice, and I think both function as femme fatale, at least in a certain way. Alice clearly has the most basic qualities of the femme fatale, because she acts at the same time as a desire for Oliver and as a threat to both Oliver (who may be in danger because Alice’s love for him may unleash Irena’s wrath) and Irena (whose jealousy can trigger things that may be dangerous for herself). Irena can be seen as a more peculiar femme fatale, because she too is at the same time a desire for Oliver as a threat to him. You could say that in a certain way the cat (or the ghost of a cat) inside Irena is the true destructing part of the femme fatale and Irena herself the seducing part of it; both combined form a complete femme fatale, despite the fact that this femme fatale doesn’t act as such in a conscious way, but more on a unconscious level. It is interesting to note that the traditional film noir ratio of two men and one woman is reversed in ‘Cat People’, because here we have two women and only one man.

A queer reading of Cat People

It is because Irena can’t love her husband (and perhaps can’t love a man in the first place) that everything goes wrong. As author Greg Mank remarks on the DVD’s audio commentary (released as part of the Val Lewton Horror Collection) there is a lesbian subtext in the film, which has already been spotted at the time of the film’s original release. It is never made clear why Irena can’t love her husband, but the explanation that she is a lesbian is certainly a possible one. This is given more substance in the scene of their wedding night, when a strange woman approaches Irena and speaks to her in a strange tongue, a scene which has a decidedly gay subtext, although it could never be made explicit of course (because of the Hays Code). When we look at Richard Dyer’s ideas on homosexuality in film noir, he concludes that most film noirs portray homosexuality as a sickness, and gay people are always portrayed as villains. When we read ‘Cat People’ in a queer way, it is apparent that Irena’s lesbianism may be at the core of her sickness: it is because she can’t love a man but is forced by society to do so, that her troubles begin. Her homosexuality is thus the center of her emotional problems. At the same time, she is partly portrayed as the villain, because she threatens several people in the film, even killing Doctor Judd in the end. But at the same time, she is also the film’s victim, a sad figure who is trapped in her own confusing mental world, a world from which she cannot escape. So her homosexuality makes her both the victim and the victimized, so that gives this film clearly a subversive subtext; the film doesn’t point it’s finger at homosexuality itself, but at the society which doesn’t allow or tolerate homosexuality, forcing homosexuals into the closet. As such, the film can be read as a condemnation of homophobia, suggesting that intolerance towards homosexuality can lead to mental disturbance, here manifested in Irena’s transformation into a giant cat. In this way ‘Cat People’ can be read as a subversive film, which leads us to the discussion of progressive genres.

Cat People as a progressive text

The first thing I should acknowledge when I want to present ‘Cat People’ as a subversive or progressive text is that this was a B-film, so it immediately falls into Pam Cook’s defense of the B-film as more capable of social criticism. Her emphasis on the representation of women (in which she argues that women are better portrayed in B-films than in their ‘better-quality’ counterparts) is particularly useful in this respect, because, as we’ve already seen, ‘Cat People’ is pretty unusual in its representation of women. There is much less stereotyping going one than in most films from this period, particularly in the figure of Irena, (Alice is a much more conventional character, BTW) with her inner turmoil and her possible lesbianism.

As Robin Wood argues, the horror film always occupies a place outside the Hollywood system, because they ‘possess the potential, that is, to exhibit as explicit content what most other film soundly repress’ and because they have a disreputable reputation in general, they are ‘capable of being more radical and subversive in their social criticism, since works of conscious social criticism… must always concert themselves with the possibility of reforming aspects of a social system whose basic rightness must not be challenged’ (Klinger, 79). While we mustn’t forget that Wood wrote this mostly in connection with ‘70s horror films, his basic idea can very well be applied on ‘Cat People’. While this film perhaps doesn’t make explicit what other films soundly repress, it certainly does call attention to it. Because it is never explained what causes Irena’s inner turmoil, the viewer is forced to come up with his own solutions. The film offers several possible explanations (lesbianism, childhood trauma, female jealousy), but it’s deliberate refusal to explain, gives this film a potentially subversive and progressive face. ‘Cat People’ may not be as bleak, cynical or ironic as most film noirs, but it can be easily read as a precursor to the more radical later films in it’s presentation of a disjointed world and the fact that the film has no real or redemptive closure (Irena dies at the end).

Conclusion

‘Cat People’ has, as I have tried to demonstrate briefly in this paper, much in common with what has been typically been defined as film noir. Obviously, this is not a film noir in the most strict sense, if only because it never entered the film noir canon for obvious reasons: it doesn’t have the convoluted narrative, the flash-back structure, the hard-boiled hero, a true femme fatale etc. Still, I think that this film has so many tangent planes it can’t be just a coincidence. This can be explained in the fact that it’s director, Jacques Tourneur, was to become a key factor in the shaping of the archetypal film noir style with his film ‘Out of the Past’. It should therefore come as no surprise that ‘Cat People’ is in a lot of ways a precedent for the latter film. But this can’t be the only reason, if only because producer Val Lewton had as much artistic input in this film as Tourneur did. I think a lot of characteristics of ‘Cat People’ can be found in its era, in the social and economical circumstances of the time, just like most of film noir’s characteristics can; it is clear therefore that film noir isn’t the only ‘genre’ in which the situation of its time is reflected. If this short analysis can bring any conclusion it would be that it gives us yet another example for the instability of the term ‘film noir’.

February, 2006

Maikel Aarts

Labels: film noir

Regie: Robert Fuest (1972)

Regie: Robert Fuest (1972)

A cat-like shadow is seen on the wall, a gesture that will return several more times in this particular scene. The now frightened Alice jumps in the pool and the water makes ghostly reflections on the walls, again a showcase for the innovative cinematography of Musuraca. Just like in the pursue scene, the tension is largely created by the immaculate editing of Mark Robson, alternating between the frightened face of Alice and the water reflections on the wall, complete with eerie shadows.

A cat-like shadow is seen on the wall, a gesture that will return several more times in this particular scene. The now frightened Alice jumps in the pool and the water makes ghostly reflections on the walls, again a showcase for the innovative cinematography of Musuraca. Just like in the pursue scene, the tension is largely created by the immaculate editing of Mark Robson, alternating between the frightened face of Alice and the water reflections on the wall, complete with eerie shadows.